Drawings for ‘Codices Madrid’ by Leonardo da Vinci

[Zeichnungen zu 'Codices Madrid' von Leonardo da Vinci]

- 1975

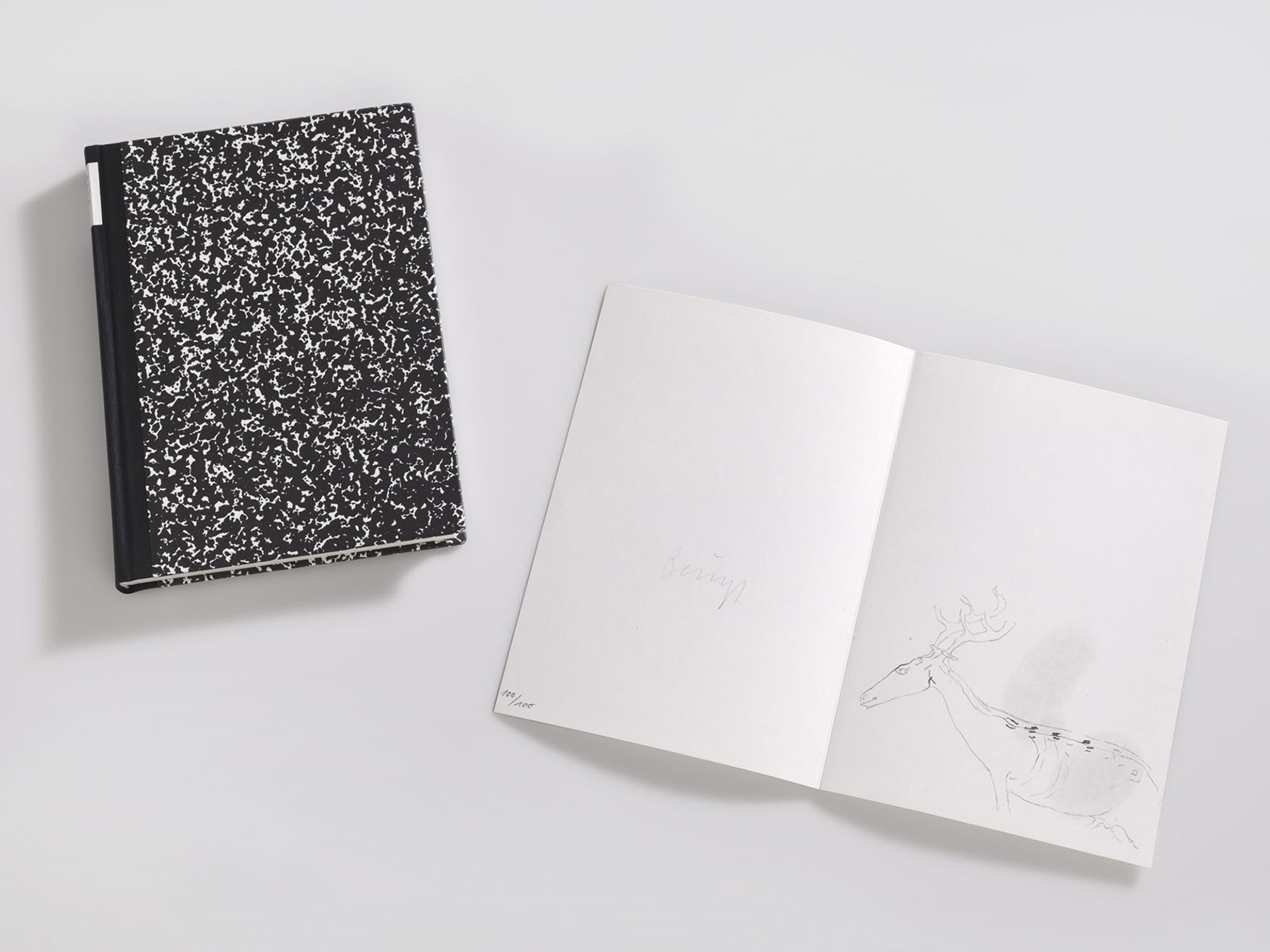

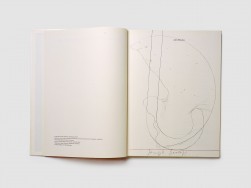

- Book with 81 granolithographs, 156 pages, half-cloth

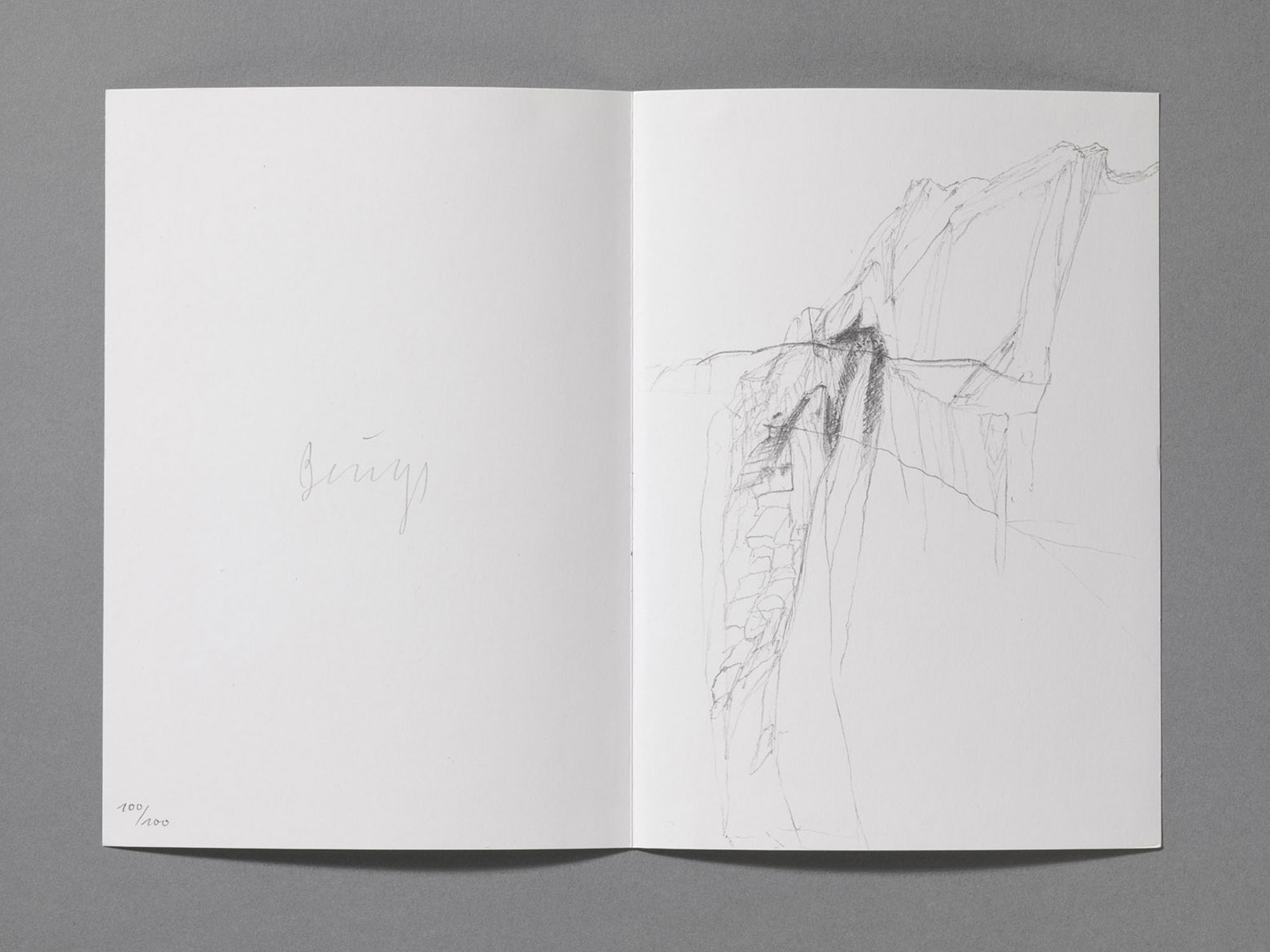

23 x 16.5 cm - Edition: 1000, numbered. Copies 100–1000 including a granolithograph, 23 x 32 cm, folded to book format. Nine different motifs. 100 of each motif, signed and numbered

- Publisher: manus presse, Stuttgart

- Catalogue Raisonné No.: 177–185

This book comprises Beuys’s response to two lost volumes or ‘codices’ of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, which were discovered in Madrid in 1965 and published in facsimile editions in 1974.1 Featuring 81 lithographs, reproducing pencil drawings by Beuys, it offers several suggestive parallels between the two artists’ works, while also affirming important points of difference.

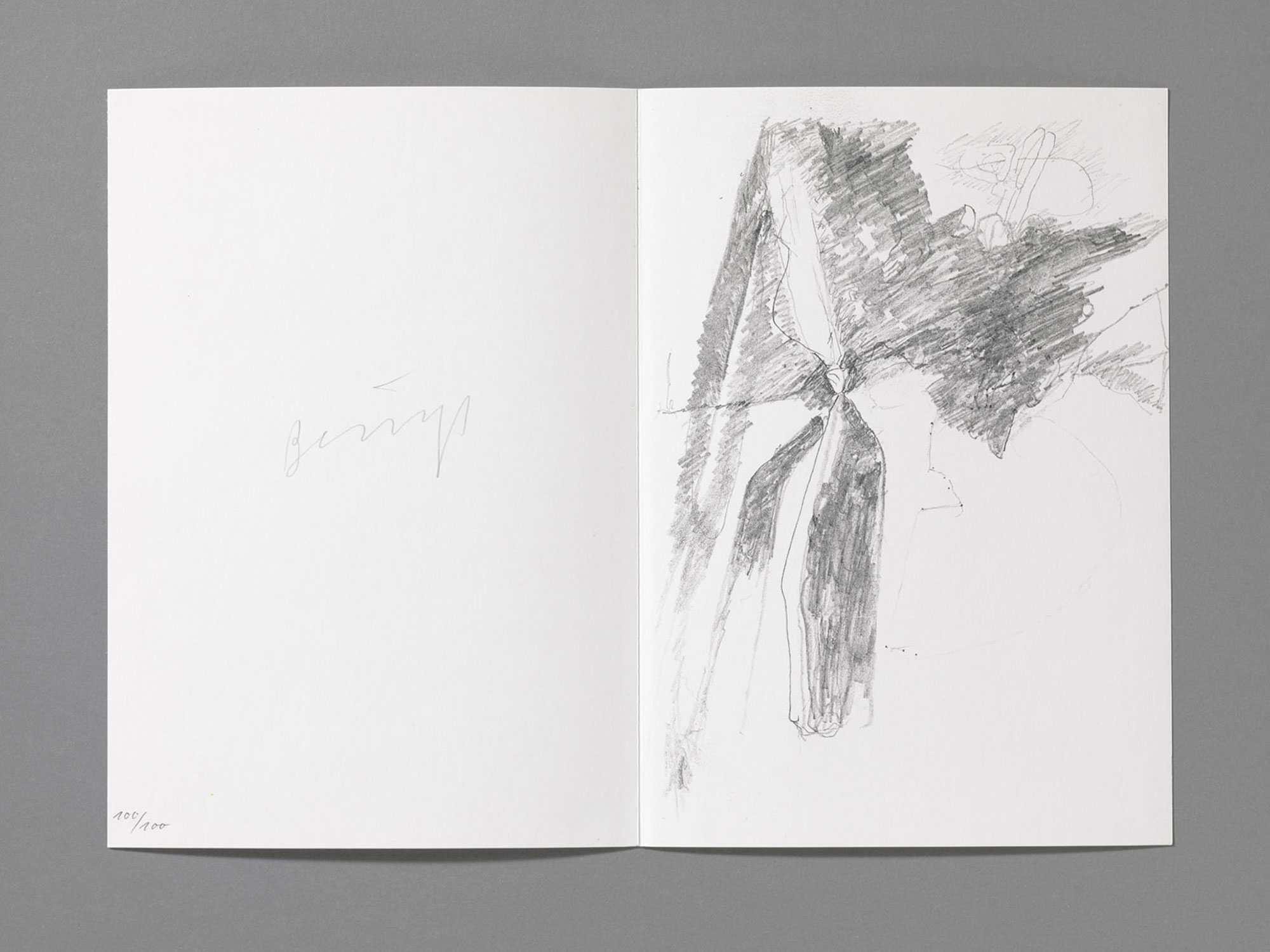

Most of Beuys’s drawings describe the flow of energies within and between different forms, including landscape motifs, human bodies and, occasionally, highly abstract machines. Delicately rendered with filigree-like linear inscriptions and intermittent patches of dark shading, these figural motifs are riven and connected by free-ranging vectors of pure force. Together they are redolent of two types of drawings for which Leonardo is well-known, each amounting in its own way to a kind of energy-flow diagram: his studies of machines and his efforts to illustrate the movements of water. But whereas Leonardo’s forms were exactingly described and instantly recognisable, Beuys’s figures are rich in associative qualities but seldom explicitly depictive. Such contrasts emerge in large part from divergent drafting methods. While Leonardo’s images were carefully conceived and methodically committed to the page, Beuys’s working process was a good deal more intuitive and improvised.2

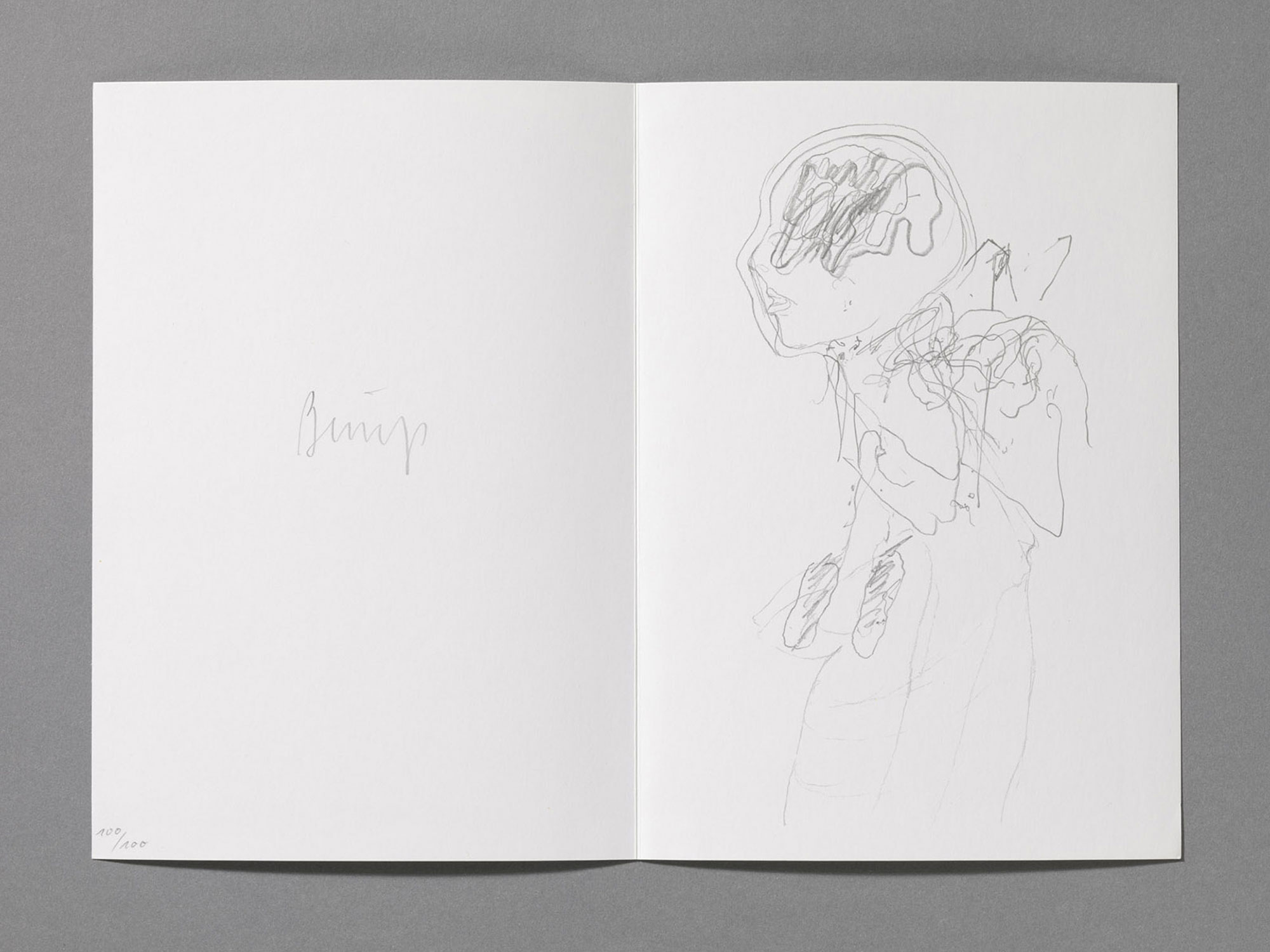

The two artists’ images of bodies help bring this distinction into clearer relief. While both favoured frontal or side-on depictions of the body in their drawings, Beuys’s interest in anatomy was rooted less in techniques of precise, scientific observation than in processes of symbolic and spiritual evocation. Thus, when Beuys sketched the uterus and ovaries of a female figure, he was not attempting an exacting physical depiction. Instead, he was attending to the life-giving regions of the female anatomy, which to his way of thinking infused matter with the spiritual energies of consciousness.

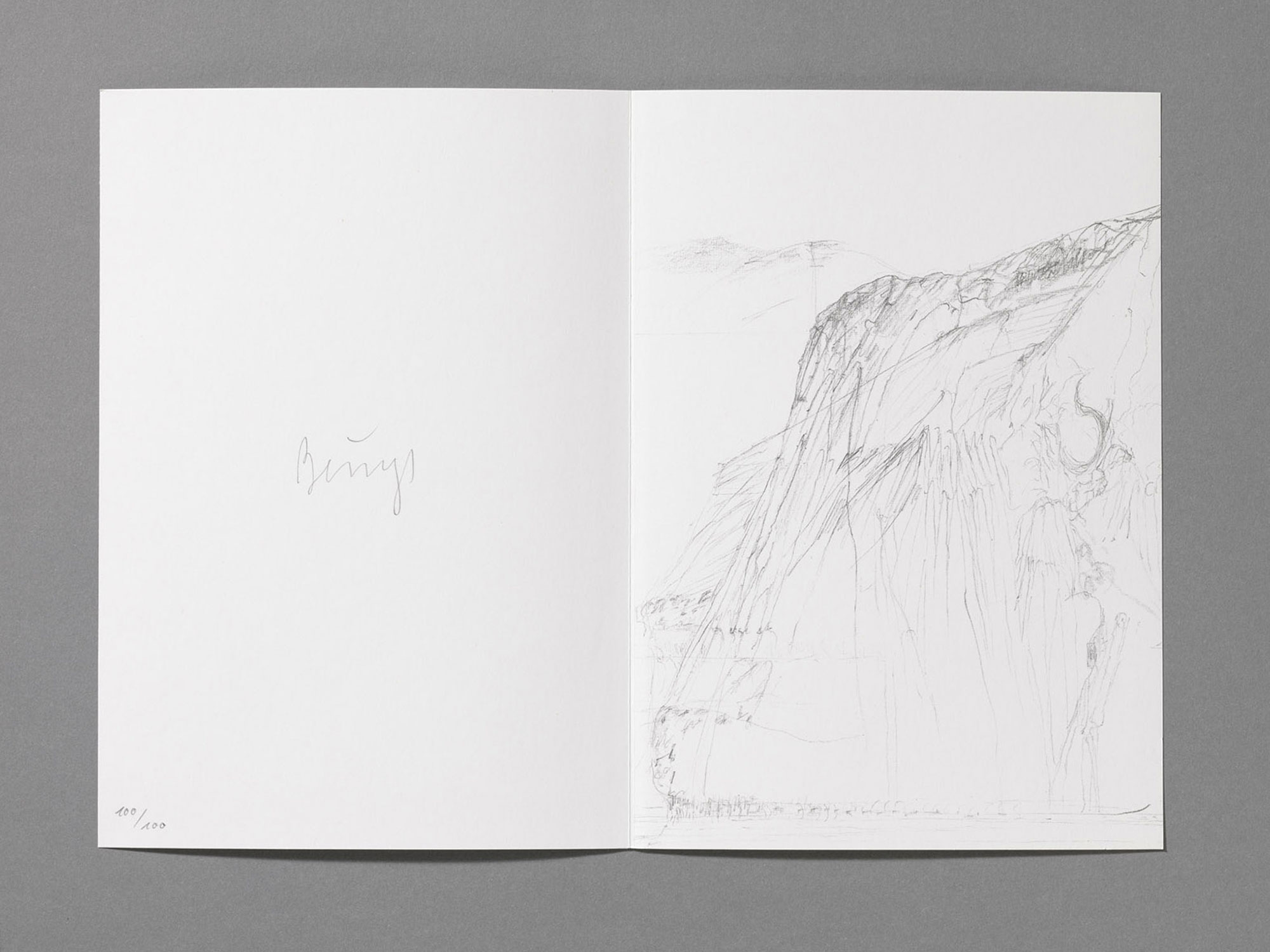

The many landscape images in Beuys’s sketchbook also evince this spiritual focus. His depictions of mountain ranges, for example, feature scrawled and scribbled fault-lines that call to mind the slow-moving energy dynamics of geological activity.3 For Beuys, interactions such as these offered evidence of ‘underground spiritual energies’ rather than the physical activities that held Leonardo’s attention.4

In contrast to Leonardo’s codices, whose contents remained private, Beuys’s book, like all his multiples, was intended for public circulation. As if to underscore this intention, the format of Beuys’s book is unorthodox. Instead of being bound in cloth or leather, as is typically the case with facsimile editions, its cover is made from simple printed cardboard, whose black and white patterning derives from an American school notebook.5

The first 100 of the book’s 1000 copies included an additional portfolio of 12 further lithographs, with the remainder featuring one of nine possible additional lithographs.

On the history of Beuys’s project and the origins of the drawings contained in his Leonardo book, see Cornelia Lauf, ‘Multiple, Original und Künstlerbuch: Die Codices Madrid,’ in Lynne Cooke and Karen Kelly (eds.), Joseph Beuys: Zeichnungen zu den beiden 1965 wiederentdeckten Skizzenbüchern “Codices Madrid” von Leonardo da Vinci (Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 1998), 39–40; and Ann Temkin, ‘Joseph Beuys: Codices Madrid,’ ibid., 13. ↩As Martin Kemp has noted, however, there is a shared tendency on the part of both artists to use the drawing process as a means of intellectual exploration, employing the sketchbook format as a forum for creative experiments that may or may not be realised in real life. (See Martin Kemp, ‘Leonardo-Beuys’: Das Skizzenbuch als Experimentierfeld,’ in Lynne Cooke and Karen Kelly (eds.), Joseph Beuys: Zeichnungen zu den beiden 1965 wiederentdeckten Skizzenbüchern “Codices Madrid” von Leonardo da Vinci, 31–38.)

Beuys spoke on one occasion of wishing to emulate this aspect of Leonardo’s codices, which he admiringly described as ‘technical catalogs of possible things’ rather than neat compendia of existing subjects. (See Martin Kunz, ‘Gespräch mit Joseph Beuys,’ in Joseph Beuys. Spuren in Italien (Luzern: Kunstmuseum Luzern, 1979), n. p.) ↩Beuys’s wife Eva had studied these dynamics at Düsseldorf Art Academy in the late 1950s, where she had written her graduation thesis at the on the role of background landscapes in Leonardo’s painting. For the book that resulted from her research, Beuys created diagrams outlining the main flows of energy among the natural formations and human figures in Leonardo’s work.

See Eva Beuys-Wurmbach, Die Landschaften in den Hintergründen der Gemälde Leonardos (München: Schellmann & Klüser), 1977. ↩See Martin Kunz, ‘Gespräch mit Joseph Beuys’ in Joseph Beuys: Spuren in Italien, n. p.) ↩

Ann Temkin notes that the design of Beuys’s book derived from an American school notebook purchased by Caroline Tisdall in New York. (See Ann Temkin, ‘Joseph Beuys: Codices Madrid,’ in Lynne Cooke and Karen Kelly (eds.), Joseph Beuys: Zeichnungen zu den beiden 1965 wiederentdeckten Skizzenbüchern “Codices Madrid” von Leonardo da Vinci (Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 1998) 21, n. 33.) ↩

© H. Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen